‘A group of people passionate about … development.’

By Dr Janke Gryta.

From the Institute for Development Policy and Management to the Global Development Institute: a history of Development Studies at The University of Manchester since the 1990s.

Introduction

To celebrate the end of the 2017–18 academic year, the Global Development Institute (GDI) organised a Q&A session for its soon-to-be graduates. The panel consisted of Dr Pablo Yanguas, Prof Diana Mitlin, Prof David Hulme, Prof Richard Heeks, Prof Khalid Nadvi and Dr Helen Underhill. These men and women, all experts in their respective fields, represented different nationalities and ethnicities. In fact, they were only a tiny fraction of the Institute's diverse staff. Currently GDI has over 45 academic staff members, from five continents and 18 countries, nearly 100 PhD students and over 400 master's students, representing a variety of cultural backgrounds. From the composition of its staff body through to the global impact of its research, and even to its location in one of the most multicultural cities in the UK, the Global Development Institute truly lives up to it name. However, it took 60 years to build this position.

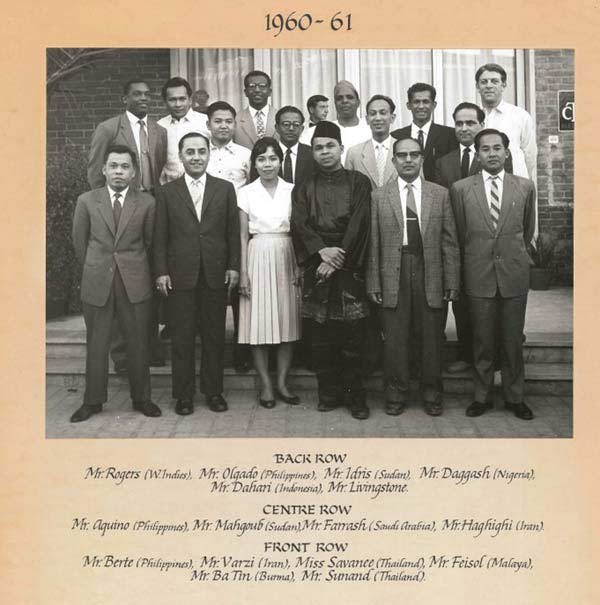

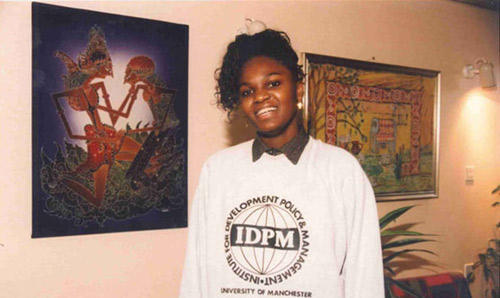

GDI, in its previous institutional guises as the Department of Overseas Administrative Studies (DOAS, 1963–83), the Department of Administrative Studies (DAS, 1983–87), the Institute for Development Policy and Management (IDPM, 1987–2016) and the Brooks World Poverty Institute (BWPI, 2005-2016), had not always boasted such a diverse staff, nor was it always a globally recognised centre for Development Studies. Indeed, its beginnings can only be described as humble. It started off in 1958 not even as a Department, but as a one-person institution, tucked away in the University. Arthur Livingstone, the founder of what would become the Department, was given one small room in which to run his first programme (Newslink, 2005, p 9). At the time Development Studies at the University, as in the rest of the UK, were very much rooted in British colonial history. Some of its first instructors were ex-colonial administrators with a remit to teach officials from the newly independent countries how to run their governments (Clarke, 1999, pp 521–522). Yet what started as the informal Public Administration Course for Overseas Government Servants evolved to be the modern-day GDI. How? The early years of this history were described by Ron Clarke (1999) in his 'Institutions for training overseas administrators: The University of Manchester's contribution'. The inquisitive reader also may find archival copies of Newslink, the IDPM's alumni newsletter, an equally informative source of knowledge on the Institute's early years. This article traces the latter part of the history of IDPM/GDI starting from the mid-1990s. It tells this story with recourse to archival material, to Newslinks and to broader scholarship. Primarily, however, it gives voice to the Institute's scholars past and present.

It is based on a series of interviews and tries to make sense of the Institute's history by listening to those voices.

The article, then, looks at the most recent history of Development Studies at The University of Manchester. It finds that its humble beginnings in 1958, aspects of the peculiar postcolonial ethos and Arthur Livingstone's legacy, informs, often in paradoxical ways, the workings of GDI today. The narrative presented here is very much a story of change influenced by 60 years of a rich institutional history and culture. It is a story in which there are no obvious thresholds and neatly demarcated periods. There is no 'turbulent today' and there are no 'good old days'. Instead there are changes orientated around a number of themes, which form the structure for this article.

The conviction that, through teaching and later also through research, the challenges of the developing world could be addressed and lives could be improved has guided the Institute's staff, and their work, for decades. From the 1990s, it led to a revaluation of their approach to teaching when the short professional training courses that had thus far constituted the core of the Institute's programme, became less significant and postgraduate teaching was prioritised. It gave impetus to attempts to turn IDPM into a recognised research centre, that had begun in the late 1980s but that gained new momentum around the turn of the Millennium. Taking advantage of the changing national, international and funding environments, IDPM developed into a fully-fledged research institute, establishing new research centres and bringing in new research staff. A local event, the merger of the Victoria University of Manchester (VUM) and the University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology (UMIST) had global consequences. The new University believed it could be ranked among the world's best. So did its philanthropic donors. Rory and Elizabeth Brooks, inspired by this momentum at the University and the quality of the research undertaken at IDPM (particularly by its Chronic Poverty Research Centre), supported the creation of the Brooks World Poverty Institute (BWPI). Its mission was to produce knowledge that created practical changes in the lives of people in the developing countries. BWPI successfully ran alongside IDPM, until external changes promoted a rethink. With Development Studies adopting a broader and more holistic approach, a larger critical mass of researchers was required to address and develop an increasingly complex agenda. Eventually, IDPM and BWPI merged, which also provided researchers with access to the best support infrastructure and the best means of disseminating their knowledge. GDI, the outcome of this merger, while working within a different global environment from the one in which Arthur Livingstone established his one-man institution, still adheres to the same core value. That aims to improve the lives of people living in low income communities across the globe.

The early days – the postcolonial era

Arthur Livingstone's legacy and the ethos of the early-days DOAS are still very much alive in Manchester. They set the path which eventually led to the creation of the Global Development Institute. Clarke (1999, pp 526, 522) describes Livingstone – "the doyen of directors of overseas development centres in the UK" – as a singularly focused individual who, often in adverse conditions, managed to build a stable and well-established department. However, Clarke's account also highlights Livingstone's deep interest in students' intellectual development and wellbeing, an interest that has been carried forward for decades. Conscious of differences in educational and cultural backgrounds, Livingstone committed a considerable amount of time to finding the best way to educate overseas officials and to challenge the dogmas they brought to Manchester (Clarke, 1999, p 524). He saw DOAS's mission as ensuring "a development of his [the student's] capacity to think and act constructively in circumstances that demand flexibility and ingenuity for effective resolution" (Livingstone, quoted in Clarke, 1999, p 524).

More importantly, while focusing on intellectual development, Livingstone never forgot about welfare. He was keen to reduce the distance between the study fellows (as the often mature students were called at DOAS) and the teachers.

He was always ready to take the extra step to help fellows settle down in Manchester. Clarke (1999, p 525) remembers one occasion when the teaching staff spent hours looking for a missing student all over Manchester. Wyn Reilly, the first person to be hired to work with Livingstone in 1962, notes that "we [the trainers and study fellows] got to know each other and to form friendships" (Newslink, 2008–09, p 7). Similarly, Dr Merrick Jones, who joined in 1978, talks about "the wonderfully supportive environment provided to our Study Fellows", while Dr Joseph Mullen remembers IDPM as "a group of people passionate about international development and the welfare of the study fellows" (Newslink, 2008–09, pp 5–6).

The importance of the link between education and development was another of the features of the early DOAS, one that informs the working of the GDI to this day. Professor Paul Mosley, who took over the directorship of the Department in 1986, notes that coming to Manchester made him realise that "it was possible to change the world through the enthusiasm and expertise of the IDPM's study fellows" (Newslink, 2008–09, p 6). In many ways, this sense of mission stemmed from the particular ethos of the last colonial administrators, many of whom joined DOAS and departments like it across the UK. People like Wyn Reilly and Ron Clarke helped to create the department's culture, the set of principles and values according to which its members worked in the subsequent decades. As Professor Uma Kothari, one of the leading researchers at IDPM, and its former Head, notes in her inspiring article "From colonial administration to development studies: a post-colonial critique of the history of development studies", a number of ex-colonial officers who joined British universities, had before independence worked for the Colonial Education Department or were responsible for community development and education in their respective departments (Kothari, 2005, pp 56–57).

For example, during his time in pre-independence Uganda and Malawi, Ron Clarke worked on university extension programmes (Newslink, 2008–09, p 4). Teaching was what people like Clarke, Reilly and their peers did. Combined with Livingstone's deep concern for the education and wellbeing of the study fellows, their approach created a culture particular to DOAS: a culture where, by working with individual students, equipping them with new skills and broadening their horizons, members of the Department contributed to the development of the newly independent countries.

However, the colonial pedigree, along with the education-oriented outlook also brought a set of problems, not least the perpetuation of the colonial power dynamics. Kothari mentions that some commentators see Development Studies in general as a neo-colonial project helping to maintain the dominance of the North over the South (Kothari, 2005, p 48). As this article attests, Manchester has made a conscious effort to put that part of its legacy behind it. Kothari, who joined the IDPM in 1992, was one of the first female staff members but the modern-day GDI comprises a diverse group of scholars from different ethnic, cultural and educational backgrounds. More recently, scholars from Manchester championed the shift in focus from 'international' development towards 'global' development. They acknowledged that poverty, inequality and underdevelopment are not unique problems of the 'poor South' but are universal global issues affecting, to different degrees, deprived communities in both the North and the South (Horner and Hulme, 2017).

To teach? To research? Soul-searching in the 1990s

The mid-1990s, where this story begins, were a period of change. As early as 1992 IDPM had to redefine its mission and decided on a course that would allow to evolve and thrive. Like most similar departments across the UK, IDPM offered two types of services: practically oriented training addressing very particular subject areas; and consultancy. From the early 1970s onwards, the vast majority of IDPM's teaching was organised into short, mostly 12-week, courses. With courses ranging from 'Human Resources Management' to 'Senior Management' and 'Public Service Ethics: Principles and Practice', the Department catered to the needs of managers and administrators from Asia and Africa. Its programmes were designed to supplement and build on the education and experience of professionals who had received some form of training beforehand (Clarke, 1999, pp 525–526; Newslink, 1999, p 24). The rationale for the short courses was that they were accessible to mid-career administrators. They did not require prolonged absences or a sabbatical; neither were they as expensive as a full-time degree.

Moreover, the British Council and the Overseas Development Administration, part of the Foreign Office, were keen to fund study fellows on short courses, hoping to equip them with practical managerial and administrative skills and promote British soft power (IDPM, 1999a).

The second major aspect of IDPM's work in the 1990s was consultancy. A service popular in most UK development studies departments, consultancies sent British experts to attempt to resolve practical problems in developing countries struggling with administrative or managerial issues. Willy McCourt, long-time lecturer at the IDPM and its head in the early 2000s, gives an example of one his most successful interventions:

It was around 2008. A PhD student who after graduation went to work for the United Nations Development Programme in Indonesia contacted me to do some work in the province of Aceh. Not long after the 2004 tsunami there was a peace settlement between Jakarta and the Aceh separatists. For the first time Aceh had an elected governor rather than an appointed one. The UNDP was supporting the elected governor and I was brought in to […] run the process of reappointing all of the heads of the ministries. We organised an assessment centre, it took a week and it had a very high public profile. […] It was a major policy success for the governor. (McCourt, 2018)

Despite the prevalence of short course and consultancy work, some members of staff were attracting research funding and organised international, cooperative projects already in the 1990s. For example, Colin Kirkpatrick, one of the two IDPM staff who by that time already boasted the title of professor, ran the Finance and Development Research Programme, which started in 1992 (IDPM, 2001b). One of the early international partnerships, started by David Hulme, the other of the professors at that time, was with BRAC, a Bangladeshi nongovernmental organisation (NGO) that eventually grew to be the world's biggest. BRAC focuses mainly on fighting poverty across Asia, Africa and the Americas. It benefited from Hulme's research that found microfinance was not an effective approach to helping the poorest of the poor. Says Imran Matin, one of BRAC's directors and a long-term collaborator with IDPM/GDI:

In the early 1990s David was involved in a big, international research programme on microfinance. That's when our relationship started. It was very important for BRAC because it helped us to understand some of the limitations of microfinance. […] It made us think beyond microfinance – that was something that came out of the early engagement with IDPM. (Matin, 2018)

However, influential research was only becoming a priority for IDPM in the early 1990s. Short-term courses and consultancy, both representing the same approaches to development, still constituted a big part of the Institute's activity. They were compressed, intense periods during which IDPM staff shared their knowledge. As such, they shared similar problems and did not fit with the academic environment that emerged in the latter part of the decade.

First, the staff at the IDPM started to realise that short courses were simply not the best approach possible. Hulme reminisces:

Back in the 1980s and early 1990s I did work looking into aid effectiveness and training people in the UK. What became obvious was that having those short training courses [in the UK] to improve people's performance in specific organisations … it doesn't work. They needed to be trained in the country. (Hulme, 2018)

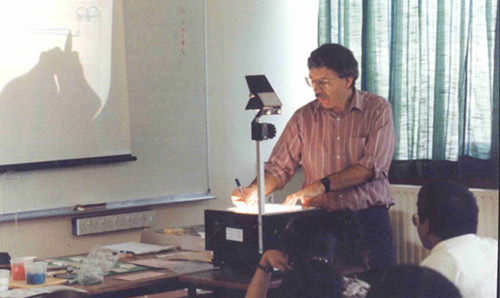

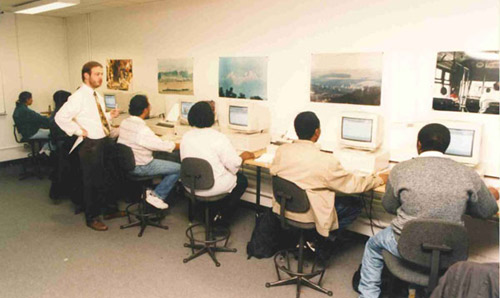

Richard Heeks, now a Professor of Development Informatics who in the 1990s focused primarily on teaching, explains that it was getting harder to convince a professional with a stable career to leave work and family for 12 weeks and come to Manchester for a course that did not offer any formal qualification.

The market just ran out. I think at the same time we continually began asking questions about why are we getting people to fly 3,000, 8,000 miles to come and be taught how to put a floppy disk into a computer. Surely there must be cheaper and better ways of doing this in a country! (Heeks, 2018)

With his background in IT, Heeks started to look into distance learning. Motivating him was:

that notion […] of going back to our traditional audience. […]We set in our mind a local government official, in a small town in Uganda. This is our person and we need to make sure that distance learning is accessible to them. (Heeks, 2018).

Gradually the answer to the short-course dilemma was resolved by the introduction of Master and Diploma programmes, most of which were Manchester based, some of which were offered via distance learning. The first Diploma was opened as early as the 1970s and the first Master's in the 1980s, but it was towards the end of the 1990s that the number of postgraduate degrees started to multiply. It grew to 13 Master's and four Diplomas in 1999 and stabilised at 20 Master's programmes offered by the modern-day GDI (Clarke, 1999, p 527; Newslink, 1999, p 24, GDI, 'Taught master's courses', nd). To complement those programmes, IDPM started to offer opportunities to obtain a PhD as well.

The second reason for IDPM to move towards more standard, academic forms of university teaching was the change in the makeup of the Institute and the growing pressure from the University to 'professionalise'. Initially, the majority of staff members had practical experience of teaching in the colonies but they were not researchers. Gradually, new staff were hired. Most of the newcomers followed a typical academic route from research degrees into lectureships. Unsurprisingly, they were often keen to pursue their research but this stood at odds with the existence of the short programmes and consultancy. Both forms were extremely demanding and time consuming, and left little time for research. This problem was already visible at the time of Clarke's appointment in 1975 (Clarke, 1999, pp 525, 527). Clarke notes that in the 1970s there were only "two or three staff" who regarded themselves as academics, as opposed to trainers. They committed to running the only Diploma programme offered at that time as it allowed them to manage research time better (Clarke, 1999, p 526).

With the growing number and influence of academics, during the late 1980s and most of the 1990s, IDPM slowly re-orientated itself towards the classical academic model, where teachers were also researchers. The academics found support in the changing environment at the University. Ron Clarke (1999, p 528) explains that "the general pressure for greater research output in academic departments in recent years [ie the 1990s] through [Research Assessment Exercise] RAE funding has of course provided a major incentive". Starting with Paul Mosley (Head of the Institute between 1986 and1992), who himself had worked for the Ministry of Planning of the Kenyan government, Heads of Institute prioritised research. Indeed, both David Hulme, who ran the IDPM between 1992 and 1997 and Colin Kirkpatrick, in charge between 1997 and 2003, came from a more traditional academic backgrounds. This gradual reorientation towards research, while eventually successful, did not go unopposed. Kirkpatrick remembers that one of the greatest challenges for him was resolving these tensions.

[…] you did have a substantial number of staff who'd been there for some time […]. Duties which they have been required to perform were shifting because we were moving out of the professional training programmes […] and the accountability in terms of your research work, research funding, your postgraduate teaching was becoming more and more important. And this presented some challenges to the staff that had been appointed in entirely different conditions. As a Head of Institute, this was one of the most challenging human resources issues which I had to deal with. (Kirkpatrick, 2018)

Understandably, changes in duties caused some tensions but, in the long run, the remaining IDPM staff appreciated the course of this evolution. Heeks, who moved from a position of trainer to that of a researcher and a lecturer, explains that for him the change was beneficial. "I'm perfectly happy how things are because necessarily time we don't spend on one thing we spend on another" (Heeks, 2018).

Time that had previously been invested in short-term courses could now be allocated for research. For Heeks this has profound consequences and translated greatly into his teaching practice. He goes on to explain that initially he "[…] was kind of a computer trainer" (Heeks, 2018). In fact,

I don't think I would have ever described, when I was talking to people about where I worked, I would have never have said I work in Development Studies back in the 1990s. Generally, I told people I did stuff to do with IT. I didn't really bring the development stuff very much because, being blunt, teaching somebody from Nigeria how to use Microsoft Excel is really not that different from teaching somebody from Stockport how to use Microsoft Excel. So that 'developmentness' of the Institute was also increased over time. Our engagement with theories of development, with ideas of development, notions of why developing countries are different from the Global North have emerged over time. (Heeks, 2018)

For Heeks, the addition of research meant a move "from being a development training institute to being a Development Studies institute".

The final problem with the focus on the short courses and consultancy lay in their financing. Relying on this type of income proved to be the undoing of a number of Development Studies institutes across the UK. Towards the 1990s the market started to change. Consultancy was pushed to the background, despite the University's enthusiasm for focussing IDPM on consultancy in the former Soviet Union, and the approach to teaching was revolutionised. Heeks and Hulme were not the only people to notice that bringing students to Manchester for short programmes that gave them no formal qualification was hard to justify. Up to this point the main funders (via grants for students) of the short programmes had been the British Council and the Overseas Development Administration (part of the Foreign Office which in 1997 was transformed into the independent Department for International Development – DfID). In the late 1990s both organisations started to cut their spending on short course teaching (IDPM, 1999a). In consequence, throughout the late 1990s the number of students on short programmes continued to drop. IDPM put a lot of effort into promoting these courses but year after year, more had to be closed (IDPM, 1998;1999b). At the same time, the number of students on postgraduate programmes, Master's and Diplomas, continued to grow (IDPM, 2000a). However, thanks to the move towards research, the Institute managed to survive and succeed.

Towards the end of the 1990s it was all going horribly wrong. Everyone was closing; all these places that had divided their departments into consultancy wing and Development Studies programme. Swansea had its consultancy wing and Development Studies programme. That was the place to go to if you wanted to do a Master's in Development and that just went… Nobody could survive in the environment which became more and more about research. We were anxious, we were worried […] the world was changing and it was impossible for us to carry on. (Kothari, 2018)

The expectation that IDPM and institutions like it would become research centres as well as education centres emerged gradually during the 1990s with the RAE, the predecessor of the Research Excellence Framework (REF), having a growing impact on British Universities. But the gradual evolution sped up, indeed turned into a revolution, in 1997 with the creation of DfID.

Embracing research, enhancing teaching

In 1997 Labour came to power and turned the Overseas Development Administration into the independent DfID. Clare Short served as the Secretary of State for International Development, a post which afforded her a cabinet position (Hulme, 2009, pp 21–22). Described as a 'larger than life' figure, Short revolutionised the way her new Department operated. Elsewhere, Hulme describes in detail her involvement in the formulation of the UN's Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and the efforts she took to promote the MDGs, and their earlier OECD incarnation, both nationally and internationally (Hulme, 2009, p 22 et seq). The Goals summarised neatly, in news-bite-friendly fashion, the international development agenda at the turn of the Millennium. Short used the MDGs as focal points for public understanding and managed to generate new momentum for development work. More importantly, she also revolutionised DfID spending. Hulme remembers that she was surprised when, upon starting her job, she was informed that relatively little research was done to improve the Department's work (Hulme, 2018). This would now change. The first sign of the new approach was her 1997 visit to IDPM. Hulme remembers that he "[…] was running a conference which was precisely six weeks after she has been appointed and she accepted and came here. You always get ministerial minders and she just turns up by herself and delivered an insightful speech on how universities could support development efforts" (Hulme, 2018). The feeling that it was a momentous occasion was widespread. Uma Kothari: "That was a key moment for us. We felt so amazed. She came and she was going to change things. Really going to change things. And I really think it made a big difference for us" (Kothari, 2018).

Short wanted to prioritise research and, as a result of the "Mosley effect" – as some of his colleagues refereed to Paul Mosley's "revolutionary" embrace of research (Newslink, 2008–09, p 5) – and of the efforts of Hulme and Kirkpatrick, IDPM was ready to undertake big research projects. DfID funding, in the first instance, came in the form of short- and medium-term support for individual research and relatively small projects (Newslink, 1999, p 6; 2000, p 6). Soon, however, DfID unveiled a major funding scheme; it wanted eight centres of excellence in research to be organised across the country. Hulme remembers:

They [DfID] wanted big research centres. And we got two of eight centres that were being advertised. […] Six of those eight were pre-identified. They said what they wanted. Two of them were open for self-design. You could say what was needed and the Chronic Poverty Research Centre was needed. […] I'd been talking with colleagues, we'd been brainstorming in Manchester, Bradford and Birmingham, and then one Saturday morning I woke up early and started writing and by midday the proposal was finished. (Hulme, 2018)

The creation of the Chronic Poverty Research Centre (CPRC) and the Centre on Regulation and Competition (CRC) had transformative consequences for IDPM. First, it allowed the Institute to grow at an unprecedented rate. Kirkpatrick notes that "in 1999–2000 we had 19 academic and research staff and in 2003–04 we had 38!" (Kirkpatrick, 2018). Most of the new members of the Department were brought to work in the Research Centres (IDPM, 2000b). Second, the new centres proved to produce research of the highest quality. Commenting on CPRC, which he directed, Hulme explains that

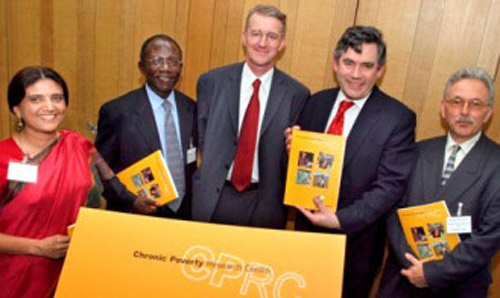

We were part of the poverty agenda but we were sort of a dissident group. [The common assumption was that] poverty was going to disappear through neoliberalisation and we said no. […] And that went down well. Our big success and what helped to really put Manchester on the map was the first Chronic Poverty Report. We did the first launch here [in Manchester] but we also had a launch in the Houses of Parliament with Gordon Brown and Hilary Benn; a very well attended session by MPs (Hulme, 2018).

The early successes of the CPRC related not only to the fact that it was recognised at the highest levels of government. It also contributed to a more critical approach, one which increasing numbers of researchers in Manchester started to present. Hulme mentioned that the researchers from the CPRC were ready to challenge the most widespread ideas about poverty reduction. Kothari explains that the same spirit spread throughout IDPM. She remembers the stir caused by one of the projects she co-ran with Bill Cooke:

[…] when Bill Cooke and I ran the workshop on participation as new tyranny, we received almost hate mail. […] People were really angry about it [but we realised that] we don't have to follow what the formal aid organisations say. We can be critical of the World Bank! We can be critical and as academics, we should be. (Kothari, 2018)

Kothari refers to their book, Participation: The New Tyranny?, which challenged the widespread, and 'fashionable' to quote its blurb, dogmas about participation. It brought into the limelight case studies in which participation had an effect opposite to the desirable; instead of promoting equality it perpetuated entrenched power dynamics and existing inequalities.

The move towards research did not mean that teaching was neglected. To the contrary, the number of students matriculating on the Master's and Diploma programmes grew, student quality increased, PhD students were registered and the staff continued to invest time and effort into new types of teaching (IDPM, 2001a). Moreover, some old practices were continued. One of the features of the teaching offered in Manchester was its focus on fieldwork.

A mainstay since the inception of DOAS, fieldwork had two main functions. It was a vital part of the training, and an opportunity to forge close bonds between students and staff; bonds that survived decades and often served as the basis for successful future cooperation. The educational dimension always came first. In the UK, the students had an opportunity to go to London to observe the work of central institutions; to Edinburgh to witness how local government operated; or to pre-Troubles Belfast to experience 'a microcosm of the UK system' (Newslink, 2008–09, p 7). Wyn Reilly remembers that "it would be unthinkable to arrange interviews with a Permanent Secretary [in London] but in Stormont it was possible", thus providing the students with an invaluable insight into the work of top state officials (Newslink, 2008–09, p 7). Some trips took students outside the UK. These were valued as they allowed students to experience conditions which they often described as much more similar to those of their own countries. Reilly remembers how important this was for one of his students, who noted that "this visit to Greece has given me hope. If we really try, we could reach this level of development" (Newslink, 2008–09, p 7).

As well as constituting an important part of teaching, fieldwork was a unique social opportunity. Jayne Hindle, at DAS/IDPM between 1985 and 2004, explains that:

It was often the thing that students really, really remembered. Not least because of the exposure; they got to see projects in developing countries, but also because they bond as a unit and they got to know staff in the IDPM very well. (Hindle, 2018)

Fieldwork trips constitute an important aspect of the education at GDI to this day.

New Millennium, new research, new Institute

In the first years of the new Millennium IDPM consolidated its strengths in teaching and research. It also underwent a structural revolution which, though at times criticised, paved the way for new opportunities. In 2004 the VUM merged with UMIST. During the merger IDPM had to adapt to a new structure. Previously as part of the VUM, the Institute enjoyed a significant degree of autonomy. It had its own budget and was allowed to make most key decisions on its own. Simultaneously, however, staff were on three-year rolling contracts and, as Hindle remembers, there were limited opportunities for promotion, particularly for the support staff (Hindle, 2018). Independence provided a greater sense of responsibility and motivated staff (Kirkpatrick, 2018). In the long run, however, the closer relationship with the University gave the IDPM stability and allowed staff to develop research in a more secure environment.

The merger and creation of The University of Manchester brought not only institutional changes but also generated new momentum and enthusiasm for the future. Hulme highlights the importance of this feeling:

The merger really changed things. There was this idea that it was no longer a good red brick provincial University. It was a global university… in global higher education… leading global research. […] For five years, that was a really powerful narrative which did change behaviour. (Hulme, 2018)

For development research this new opening proved to be especially beneficial as it attracted new donors: Rory and Elizabeth Brooks. As philanthropists they had already been working with the pre-merger UMIST and after 2004 started to look for new opportunities to support researchers at the University. Indeed, Rory Brooks "was excited and impressed by the vision for the new University – under the leadership of Alan Gilbert – to create areas of world-class excellence in certain fields" (Brooks, 2018).

Hulme remembers that:

I was fortunate to meet a representative of him [Rory Brooks]. …she came for a chat and a cup of tea and to talk about South Africa. I [...] mentioned that I'm running the Chronic Poverty Research Centre […]. We have £2.5 million funding but I have another million worth of projects that I can't fund but that are totally brilliant. A few weeks later the Alumni Office called and asked if I could put on a jacket and have lunch with Rory Brooks. (Hulme, 2018)

The discussion soon moved from aiding a few CPRC projects into funding a new research institute, and eventually the Brooks World Poverty Institute was designed. Envisaged as a research institution, it was apart, an addition to IDPM. Rory and Elizabeth Brooks decided to fund the Institute because of the strength of the research already done at the University in general and the CPRC in particular. They also appreciated the particular approach to development impact via research, policy advocacy and teaching that was part of the IDPM's approach. Kothari recalls that, during one of the early meetings, Elizabeth Brooks asked directly "why don't we just give money to the woman who has to walk 10 kilometres to get water from the well" (Kothari, 2018). An answer was provided by the BWPI book Just Give Money to the Poor– arguing that poor people should be supported by national social protection policies not charity.

Most recently, Rory Brooks stated that he was keen 'to blend academic research with policy relevant outputs' (Brooks, 2018). The staff at the IDPM successfully persuaded the Rory and Elizabeth Brooks Foundation of the validity of their approach to research and impact but this did not mean that Rory and Elizabeth became any less engaged and inquisitive. In fact, they accompanied researchers into the field on numerous occasions. Nicola Banks, one of the first doctoral students not only to start her PhD at the BWPI but also funded by the Rory and Elizabeth Brooks Foundation, and now a lecturer at the GDI, remembers that Rory and Elizabeth were keen to join field researchers in Bangladesh.

They have been very engaged. […] They were always slightly concerned whether they would get value for money investing in research vis-à-vis just handing the money to NGOs. And that in a way is a very good suspicion to have. It means that you have a vested interest in making sure that what you're doing is making a difference and is world-leading and is practical and influential. And for me as a researcher that's important. […] I do a lot of policy-oriented research and you know what… there is a space for that [at Manchester]. (Banks, 2018)

Rory Brooks himself remembers the Bangladesh trip as "particularly enlightening and quite challenging" (Brooks, 2018).

The opening of BWPI added to the momentum initiated by the creation of the DfID-funded research centres at the beginning of the Millennium. New staff was brought in; the number of doctoral students grew as well. Towards the end of the 1990s there were only two professors at IDPM. Today, the GDI list 14 scholars of professorial rank (GDI, 'People', nd).

Among the scholars associated with the Institute was Nobel Prize winning economist Professor Joseph Stiglitz, who served as BWPI chair between 2005 and 2010. Hulme explains the benefits of bringing Stiglitz on board:

We got Joe to do great summer schools for PhD students and major public lectures. […] He helped us mount events at Columbia in New York, in Johannesburg, and in a number of other locations. […] Getting half a day of Joe's time if you're doing an event anywhere is very useful because of his convening power … You know, you're going to get a much bigger crowd. (Hulme, 2018)

And there was indeed a lot to promote. Stephanie Barrientos' project, 'Socio-economic Mapping of Cadbury Cocoa Chocolate Value Chains,' the 'Effective States and Inclusive Development Research Centre', and Armando Barrientos', David Hulme's and Joseph Hanlon's book Just Give Money to the Poor: The Development Revolution from the Global South were some of the influential and interesting projects run by Manchester academics at that time.

Stephanie Barrientos spearheaded a group of international researchers who analysed the impact of various means of cocoa production on farmers and communities in Ghana, the Dominican Republic and India. This project, unique in design and execution, was commissioned by Cadbury/Kraft and run between 2006 and 2011. It offered new insights into the socioeconomic background of the production of chocolate. It also incentivised first Cadbury, and later other major chocolate producers, to shift towards Fairtrade cocoa. The move had practical and direct effects on cocoa farmers' lives and wellbeing. For example, "cocoa yield in Ghana has increased by 20%, while household incomes have also risen" (GDI, 'Cadbury invests', nd).

The Effective States and Inclusive Development Research Centre, created in 2011 and with funding now secured until 2019 is a truly global research network. Funded by DfID it is a partnership of 16 organisations from Europe, North America, Africa and Asia. International in scope, it is run from the GDI with David Hulme serving as its CEO and Professors Sam Hickey and Kunal Sen working as Research Directors. Its principal subject of research is to determine how the politics that underpin inclusive development can be promoted. Researchers from the centre examine the role of the state and the impact of elites in an effort to determine how best to promote inclusive development (ESID, 2018).

The 2010 book Just Give Money to the Poor co-written by Hanlon et al had effects that surprised them all. The book demonstrated the political and economic feasibility of direct cash transfers as a form of aid for chronically poor people in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia.

The findings in themselves challenged neoliberal dogmas. But what was truly surprising was the reception of the project.

Says David Hulme:

Armando and I did a seminar for 70 people at the World Bank and they wanted us to come back next month and do another one. We joked that we had done something wrong! We're not aggravating the World Bank anymore! (Hulme, 2018)

Hulme and Barrientos were among the first to demonstrate the effectiveness of these types of support programme, encouraging significant additional investment from both donors and national governments. Since the early 2000s, following the creation of CPRC, Manchester has set out an innovative agenda that at times provoked, at times was recognised for its value but ultimately contributed to a change in thinking about development. The growing momentum of the research pendulum led to another change. The Institute for Development Policy and Management and the Brooks World Poverty Institute evolved into the Global Development Institute. The change was not just a matter of simple rebranding. Neither was it a public relations exercise. Rather it stemmed from the conviction that development studies needed to abandon old, postcolonial geographies if they were to successfully engage with the contemporary causes of underdevelopment. As Rory Horner and David Hulme (2017, p 2) noted in their recent 'From international to global development: new geographies of 21st century development', the idea that underdevelopment is a problem of the Global South has recently been abandoned by a growing number of international organisations, policy advocates and scholars. They stated that "the contemporary global map of development appears increasingly at odds with any idealised binary notion of a clear spatial demarcation between First and Third Worlds, 'developed' and 'developing', or rich and poor, countries" (Horner and Hulme, 2017, p 3). This statement, grounded in a nuanced analysis of factors as varied as the changes in GDP, in access to healthcare, and in access to primary, secondary and tertiary education, led them to arrive at an interesting conclusion. They demonstrated that, while some differences between citizens of the Global South and Global North are diminishing, often rapidly, new gaps in development can be observed. Importantly these are emerging in both the countries of the Global South and the Global North. For example, 'in an extreme example of differences in life expectancy from within the UK, a 28-year gap was found between people in different parts of the city of Glasgow' (Horner and Hulme, 2017, p 20). Thus Horner and Hulme (p 3) advocated a "move beyond simplistic claims of global convergence, which ignore continuing vast and shifting global inequalities". Instead "echoing somewhat an earlier move from international health (tropical medicine) to global health (improving health and equity in health for everyone) … we suggest that ultimately a shift from international development to global development is required" (Horner and Hulme, 2017, p 25). Development is, then, not supposed to be focused only on the 'poor countries' of the 'Global South'. Rather it is "linked to the whole world" (p 26). "Moving from international to global development is a recognition that we live in 'one world' – albeit with major inequalities – and not in a 'North' or 'South' or in First and Third Worlds" (Horner and Hulme, 2017, p 22).

This new understanding of development informed the creation of the GDI. In practical terms, the Institute fully united the two previously existing entities, i.e. IDPM and the BWPI. The BWPI was designed to build on the successes of the CPRC and carry forwards its agenda when the DfID funding ran out. With the aid of the Rory and Elizabeth Brooks Foundation's generous funding it had built an extensive support infrastructure. After a decade of operation it became clear that this infrastructure could be used by the whole of the IDPM. Indeed, in the internal discussion the idea of "integrating the excellent resources" was voiced, as was the need to create a "critical mass [of researchers] in several key areas of global development" (IDPM, 'UMRI Final', nd, pp 3, 4). Moreover, merging both institutions would help with such seemingly mundane issues as simplifying the management structure and ensuring a more efficient allocation of teaching. With the complaints that "[s]taff within the more teaching-intensive parts of IDPM have also struggled to carve out the time required to sustain their research activities" (IDPM, 'UMRI Final', nd, p 4), this was an important issue.

The institutional changes, the 'integrating of excellent resources', and creation of a 'critical mass' led to the establishment of an institution that was driven by a new spirit and an even more pronounced need to make an impact on the world around it. Says Kothari, who as IDPM Head oversaw the merger:

GDI is nothing like the IDPM was. It feels different in every way: the composition of staff, the priorities, the kinds of research we do. […] Intellectually GDI focuses its work much more on global issues towards social justice, addressing inequalities … For me the GDI is much more political. I think it helps our work to have an even greater impact. We were able to create an even stronger group of researchers. (Kothari, 2018)

Kothari has been at IDPM since the early 1990s but Banks, who had joined after the creation of BWPI, talks about the GDI in similar way. From her point of view one of the features of GDI is the diversity of its outputs. She mentions that she "do[es] a lot of policy oriented research and [that] there is a space for that [at Manchester]" (Banks, 2018). Instead of focusing only on scholarly publications in prestigious journals, researchers at the GDI think first about the real world impact of their work and only then consider how it fits with the current governmental guidance for demonstrating research excellence. She cites as an example the project 'The Lived Experience of Climate Change: A Story of One Piece of Land in Dhaka' by Dr Joanne Jordan.

One of the outputs was a Pot Gan, a form of traditional folk play that combines elements of drama, dancing, music and pictures. Importantly, Pot Gans are interactive; the audience can participate in the event and, in this case, engage with local problems related to climate change. The work on Pot Gans might or might not be submitted for REF; Jordan's objective was different. She wanted to talk directly to the local communities. Indeed, the Pot Gan and its recording have thus far been seen by over 100,000 people (GDI, 'The lived experience', nd).

The success of GDI research lies not only in the culture of the Institute and the strengths of its researchers. Both Kothari and Banks draw attention to the Institute's research support and communications teams. Banks explains that the work of the communications team not only helped her to disseminate her research but also allowed her to see her work in a new light.

All of those things that you're doing are often disparate. I have a project here, another project there. I do an output here and an output there but it never really comes together. The communications team will do blog posts, they'll prod you to write one [she chuckles], they'll do all the hard work to make sure the blog is read, they'll disseminate it, do podcasts. These things work. Last week they sent me my new staff profile. They talk about my research in way that make me realise that actually, all my projects do come together! (Banks, 2018)

Indeed, the conviction that good communication helps to disseminate research and foster impact is fundamental to GDI and very much supported by the Rory & Elizabeth Brooks Foundation. Rory and Elizabeth Brooks did not cease to support the University when BWPI was merged with IDPM. To the contrary, they now assist GDI. They co-fund the communications team and they support the work of the alumni network, an important means of reaching out to the broader community involved in development work.

They also fund the Rory and Elizabeth Brooks Doctoral College, which serves not only as a doctoral training centre but also as a platform for cross-disciplinary collaboration for the researchers (IDPM, 'The Global Development Institute', nd, pp 33–36).

The GDI, the newest incarnation of DOAS , DAS IDPM and BWPI, is not only a research centre. It stays faithful to the mission present at Manchester since the inception of the University's Development Studies programme, the mission to foster change in societies and countries via education. Currently, it offers 20 different Master's programmes on topics varying from 'Development Finance' through to 'Global Urban Development' and 'International Development: Poverty, Conflict and Reconstruction'. Moreover, it constantly seeks to bring in new audiences to Manchester, always remembering about prospective students from the most underprivileged areas of the globe. Says Hulme:

One of the things that concerns us greatly is the fact that only 3–4% of our Masters students are from Sub-Saharan Africa. Forty to fifty percent of our research is on Sub-Saharan Africa. This year we [will] provide six additional scholarships for students from the region. (Hulme, 2018)

The support for students and the efficient organisation of teaching is one of the key challenges with which David Hulme, the Executive Director, and Diana Mitlin, the Managing Director of the GDI, have to grapple. One of the ideas behind the merger of BWPI and IDPM was to even out the teaching obligations of staff. However, negotiation of the pressure coming from the University, the volatile market in higher education, and the needs of research are still proving to be a problem for the GDI.

Conclusion

The Masters students and PhD students who come to our Institute come here with particular aspirations and dreams of what they want - and we help to achieve them. It's often a better career, or a different job, a better understanding of the world, a better ability to make a difference. We help them do that. We would like to be remembered for our journals and books but we also have a deeper impact on our students. (Heeks, 2018)

In his view the Institute impacts the world in three ways. First, there is the research: the big ideas about development that impact the scholarly field and resonate with policymakers. Then, there are consultancies and action research: narrow and deep intervention where researchers from GDI engage directly with communities, NGOs and companies. Stephanie Barrientos' project on Fairtrade chocolate is a good example of this. Finally, there is the very narrow and very deep impact the Institute has on the individual lives of its master and PhD students, on people who are formed in Manchester and go out to the world to change it through their daily work and effort.

The sense of commitment to students exhibited by Heeks is a legacy of the early-days DOAS, of Arthur Livingstone and old colonial administrators who came back to Manchester to educate the officials from the newly independent countries. This passion for development guided IDPM during the 1990s and the 2000s. It pushed the staff of the Institute to look for the best ways to teach, first though short-term courses, and, when those stopped being efficient, through postgraduate programmes. It also pushed IDPM towards research, a move later spurred by the changing funding environment.

The rise of DfID in 1997 symbolically sealed the reorientation from training institute to research institute. In the early years of the new Millennium IDPM attracted funding for new research centres and started to produce research that made a worldwide impact. Manchester became one of the places that set the tone in development studies across the globe. This research excellence helped to attract Rory and Elizabeth Brooks who, via their Foundation, decided to support development studies at Manchester. This led to the creation of, first, BWPI and then the merger of BWPI and IDPM to create GDI. The new Institute boasts a critical mass of researchers capable of producing world-changing research. However, it still struggles with those problems plaguing a number of other research-orientated units. Its management has to try and balance teaching obligations with research needs while at the same time following University policies. The researchers and teachers from the GDI are mobilised in this mission not only by their 60-year legacy but also by their students.

During the panel celebrating the end of the 2017–18 academic year, Yanguas, Mitlin, Hulme, Heeks, Nadvi and Underhill were bombarded with questions. The current Master's and PhD students asked about how to marry the theory and practice of development, about the importance of technology for the Global South and about how to preserve the cultures and identity of developing countries.

But the question that summed up the discussion best was much more fundamental. It pertained to what the GDI is doing to stay relevant in the changing field of development. How does it make sure that its programme is driven by the need to catalyse development and not to generate income? Only time will tell how the GDI addresses such challenges but, with its spirit, institutional history and inquisitive students, it is very well placed to do so.

Banks, N. (2018). Interview with Nicola Banks, 8 June.

Brooks, R. (2018). Personal email communication from Rory Brooks, 21 May.

Clarke, R. (1999). ‘Institutions for training overseas administrators: The University of Manchester’s contribution’. Public Administration and Development 19, pp 521–533.

ESID (2018). ‘What is ESID?’ Accessed: 13 July 2018.

GDI (nd). ‘Cadbury invests 45 million in sourcing Fairtrade cocoa Accessed: 27 June 2018.

GDI (nd). ‘People’ Accessed: 27 June 2018.

GDI (nd). ‘Taught master’s courses’ Accessed: 27 June 2018.

GDI (nd). ‘The lived experience of climate change’ Accessed: 27 June 2018.

Heeks, R. (2018). Interview with Richard Heeks, 15 May.

Hindle, J. (2018). Interview with Jayne Hindle, 24 May.

Horner, R. and Hulme, D. (2017). ‘From international to global development: new geographies of 21st century development’. Development and Change [online early view 8 December, available at https//:doi.org/10.1111/dech.12379].

Hulme, D. (2018). Interview with David Hulme, 2 May.

Hulme, D. (2009). The Millennium Development Goals (MDGs): A Short History of the World’s Biggest Promise. BWPI Working Paper 100. Manchester: Brooks World Poverty Institute.

Hulme, D. (1990) The Effectiveness of British Aid for Traning. London, ActionAid

Institute for Development Policy and Management (IDPM) (1998). ‘Minutes of the Institute’s Board Meeting’ (unpublished), 2 December 1998.

IDPM (1999a). ‘Minutes of the Institute’s Board Meeting’ (unpublished), 13 January 1999.

IDPM (1999b). ‘Minutes of the Institute’s Board Meeting’ (unpublished), 3 February 1999.

IDPM (2000a). Minutes of the Institute’s Board Meeting (unpublished), 6 October 2000.

IDPM (2000b). ‘Minutes of the Institute’s Board Meeting’ (unpublished), 5 December 2000.

IDPM (2001a). ‘Minutes of the Institute’s Board Meeting’ (unpublished), 7 February 2001.

IDPM (2001b). ‘Minutes of the Institute’s Board Meeting’ (unpublished), 4 April 2001.

IDPM (nd). ‘UMRI Final GDI Proposal’ (unpublished).

IDPM (nd). ‘The Global Development Institute – Proposal to R&E’ (unpublished).

Kirkpatrick, C. (2018). Interview with Colin Kirkpatrick, 25 May.

Matin, I. (2018). Interview with Imran Matin, 26 June.

McCourt, W. (2018). Interview with Willy McCourt, 10 May.

Kothari, U. (2005). ‘From colonial administration to development studies: a post-colonial critique of the history of development studies’. In Kothari, U. (ed.), A Radical History of Development Studies: Individuals, Institutions and Ideologies. London: Zed.

Kothari, U. (2018). Interview with Uma Kothari conducted by Emma Kelly and Christopher Jordan, 30 June.

Newslink (1999). Annual newsletter of the University of Manchester.

Newslink (2000). Annual newsletter of the University of Manchester.

Newslink (2005). Annual newsletter of the University of Manchester.

Newslink (2008–09). Annual newsletter of the University of Manchester.